Threat model

Blast-RADIUS requires the adversary to have the network access needed to act as an active adversary-in-the-middle attacker, meaning the adversary has the ability to read, intercept, block, and modify all data passing between the victim device’s RADIUS client and RADIUS server. When there are proxies between the two endpoints, the attack can occur between any hop.

This access to RADIUS traffic can happen when RADIUS/UDP packets travel over the open Internet, a practice that’s discouraged but still known to happen. When traffic is restricted to an internal network, the attacker might first compromise a part of that network, another common occurrence. In the event RADIUS traffic is restricted to a protected part of an internal network, it may still be exposed as a result of configuration or routing errors. An attacker with partial network access might also be able to access RADIUS traffic by exploiting mechanisms such as DHCP to induce victim devices to send traffic outside of a dedicated VPN

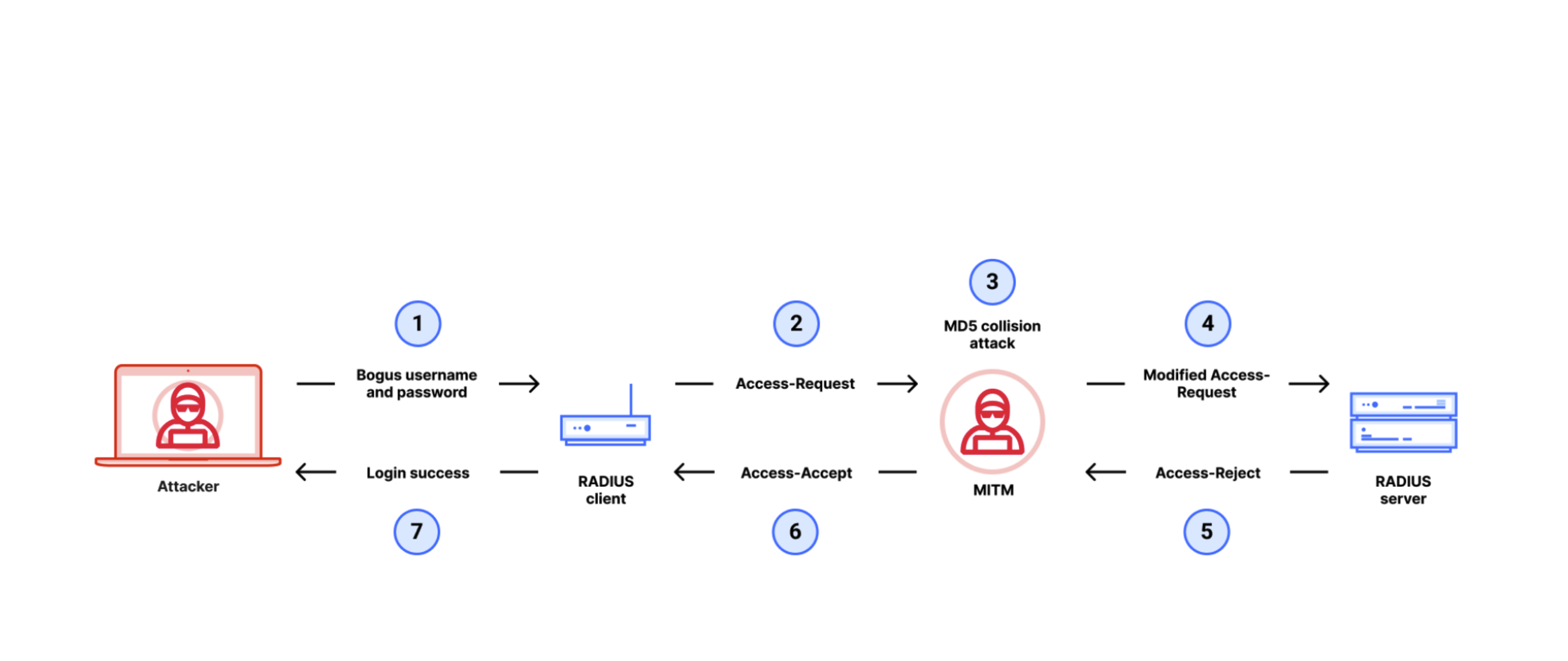

In one document accompanying Tuesday’s paper, the authors provided the following graphic illustrating the flow of a Blast-RADIUS attack along with seven key steps:

1. The adversary enters the username of a privileged user and an arbitrary incorrect password.

2. This causes the RADIUS client of a victim’s network device to generate a RADIUS Access-Request, which includes a 16-byte random value called Request Authenticator.

3. The man-in-the-middle adversary intercepts this request and uses the Access-Request (including the random Request Authenticator) to predict the format of the server response (which will be an Access-Reject as the entered password is incorrect). Then the adversary computes an MD5 collision between the predicted Access-Reject and an Access-Accept response that it would like to forge. This results in binary gibberish strings RejectGibberish and AcceptGibberish such that MD5(Access-Reject||RejectGibberish) equals MD5(Access-Accept||AcceptGibberish).

4. After computing the collision, the man-in-the-middle attacker adds RejectGibberish to the Access-Request packet, disguised as a Proxy-State attribute.

5. The server receiving this modified Access-Request checks the user password, decides to reject the request, and responds with an Access-Reject packet. As the RADIUS protocol mandates that the Proxy-State attributes are included in responses, RejectGibberish is attached to the response. In addition, the server computes and sends a Response Authenticator, which is essentially MD5(Access-Reject||RejectGibberish||SharedSecret), for its Access-Reject response, to prevent tampering. The attacker does not know the value of SharedSecret and cannot predict or verify the MD5 hash.

6. The adversary intercepts this response and checks that the packet format matches the predicted Access-Reject||RejectGibberish pattern. If it does, the adversary replaces the response by Access-Accept||AcceptGibberish and sends it with the unmodified Response Authenticator to the client.

7. Due to the MD5 collision, the Access-Accept sent by the adversary verifies with the Response Authenticator, without the adversary knowing the shared secret. Hence, the RADIUS client believes the server approved this login request and grants the adversary access.

This description is simplified. In particular, we had to do cryptographic work to split the MD5 collision gibberish across multiple properly formatted Proxy-State attributes, and to optimize and parallelize the MD5 collision attack to run in minutes instead of hours. Please read our paper (/pdf/radius.pdf) for a comprehensive description.

With that, the attacker has successfully logged in to the device with administrative system rights. The attacker does not need to wait for a real user to attempt to log in to a RADIUS client. Instead, the attacker triggers an authentication request on its own by using any password. From there, Blast-RADIUS changes the authentication outcome from unsuccessful to successful.