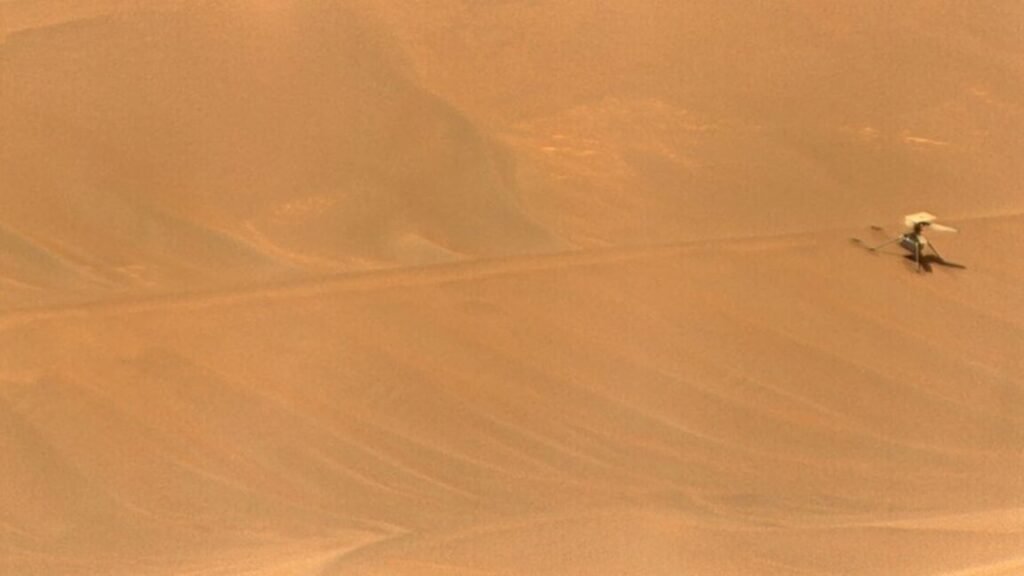

In a press release, Astroscale said observations from ADRAS-J revealed no major damage to the H-IIA rocket’s payload attach fitting, which is the planned capture point for the next mission.

After completing the fly-around maneuvers earlier this month, Astroscale may attempt to move ADRAS-J even closer to the rocket, perhaps as close as a couple of meters, to demonstrate more of the capabilities needed for ADRAS-J2.

So much debris

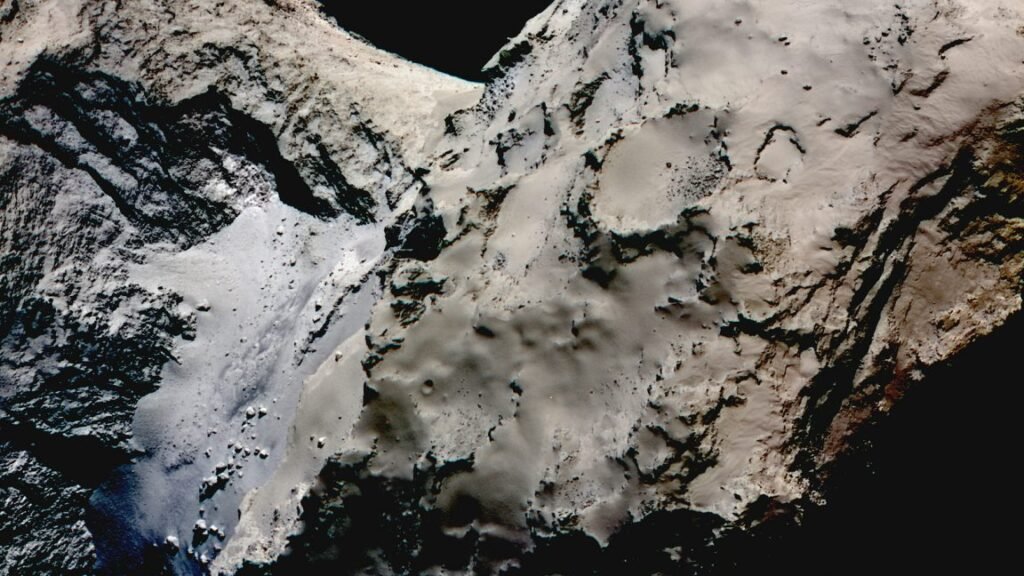

US Space Command said in December that the population of space debris in orbit has increased by 76 percent since 2019 to 44,600 objects. The uptick in space junk is primarily due to debris-generating events, such as anti-satellite tests or occasional explosions. The number of active satellites has also increased to more than 7,000, driven by launches of mega-constellations like SpaceX’s Starlink Internet network.

The European Space Agency breaks down the different types of space debris. As of June, ESA reported more than 2,000 intact rocket bodies were orbiting Earth, along with thousands more rocket-related debris fragments. Nearly half of these are in low-Earth orbit, flying at altitudes up to 1,200 miles (2,000 kilometers), where most active satellites are located. Experts have ranked these spent rocket stages as the most dangerous type of space debris because they are large and sometimes retain propellants and electrical energy that can cause explosions well after their missions are complete.

At orbital velocity, even a small fragment of debris can cause catastrophic damage to an active satellite. And these collisions beget more debris, escalating the overall problem.

The good news is launch companies are now deorbiting more of their upper stages after deploying their payloads in space. So, the number of rocket stages left behind in orbit isn’t rising as quickly as the global launch rate. But the danger from stuff already up there isn’t going away soon.

An H-IIA upper stage similar to the one visited by Astroscale’s demo mission broke apart in 2019, creating more than 70 new debris fragments in low-Earth orbit. A predicted close flyby by one of the pieces from the H-IIA upper stage prompted the International Space Station to fire its engines to move out of its path in 2020.